This post accompanies the programme booklet for Venables plays Bach, a 42-channel sound installation in l’Église de Saint Eustache, Paris, as part of the Festival d’Automne à Paris. The installation can be heard each day between 2.30–5.30pm, 7th to 16th October 2021. The live organ performances discussed here are at 8pm on 8th and 15th October, performed by Baptiste-Florian Marle-Ouvrard. Entry for everything is free. More information, and prior registration for the organ performances (because Covid) can be made here.

Twenty-five years ago, I learnt to play J.S. Bach’s Prelude in D minor BWV940, and ever since then, almost without exception, I play it every time I sit down at the piano to compose. It is the only piece that I can play from memory, with my poor piano skills, and playing this Prelude is a ritual that I go through every time I sit down to write. Improvisation often grows out of this prelude, from mistakes I make, or repetitions and variations. New music is catalysed from old music. This ritual for me is a way of focusing, shutting out other thoughts, clearing the mind, sparking ideas. Indeed, versions of Bach’s Prelude have appeared in a number of my pieces (Scene 19 in 4.48 Psychosis; the male chorus in The Schmürz).

I was asked by Festival d’Automne to make a sound installation for Saint Eustache, and so I decided to try to capture some of this compositional process. For around 50 days I recorded my daily ritual of playing Bach’s Prelude on the digital piano in my studio, complete with my improvisations, my mistakes, my singing, my tangents, my thoughts, improvisations and repetitions, as I sketched out a new piece (also for the Festival d’Automne) for mezzo-soprano and quintet, based on text by the late British poet Simon Howard. Using excerpts from these recordings, I have moulded a kind of ‘meta-composition session’ across 42 speakers in the church. Wander around and you will find small details of different days, but I hope that the whole effect it creates is an honest and reflective meditation on the act of composing, and my personal relationship to this Bach prelude.

In addition to the speaker installation, I was asked to provide a ‘live element’, and so on two evenings during the installation, the organist Baptiste-Florian Marle-Ouvrard will perform a kind of ‘exponential blossoming’ of the Bach prelude. This taps into another love of mine: the spreadsheet. I use spreadsheets in almost every piece I write, usually to chart some harmonic pattern or musical form or rhythmical change using an exponential curve. It’s an approach that I first started in 2011 with the Klaviertrio im Geiste. So for this live element, I decided to put a spreadsheet to work, to turn the Bach Prelude into a kind of ‘mathematical flower’ gradually opening up and revealing itself over a period of 28 repetitions. The idea was for the music to emerge exponentially from a point of a single note (the most recurring note in the Prelude, F4) to recreate the complete Prelude of 170 notes.

I will write below a brief method for how this was done. Suffice to say, the result is (hopefully) more of a conceptual meditation rather than a piece of music, so to speak. But one that gradually reveals the Bach Prelude over a period of around 30 minutes, emerging from a single pitch. It’s a beautiful instrument and a magical acoustic space to do this kind of thing, and I encourage the audience to come and go as they please, wander round the church and soak it up or sit down and let it wash over them.

A brief analysis of the Prelude

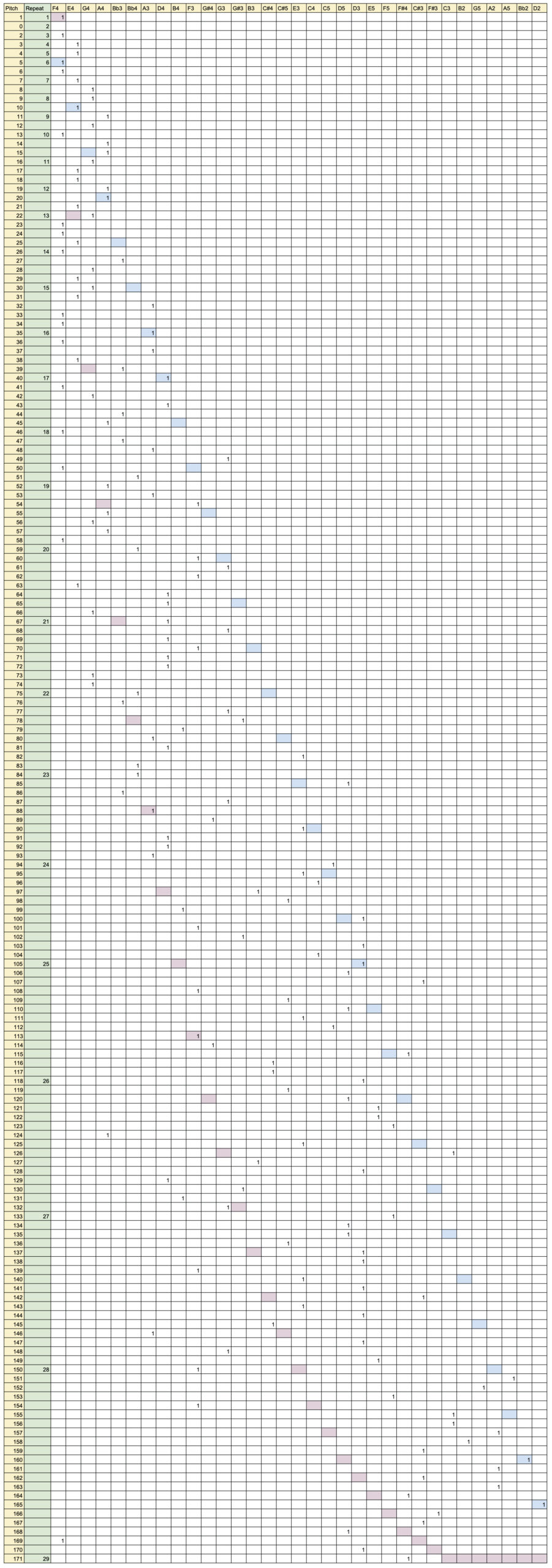

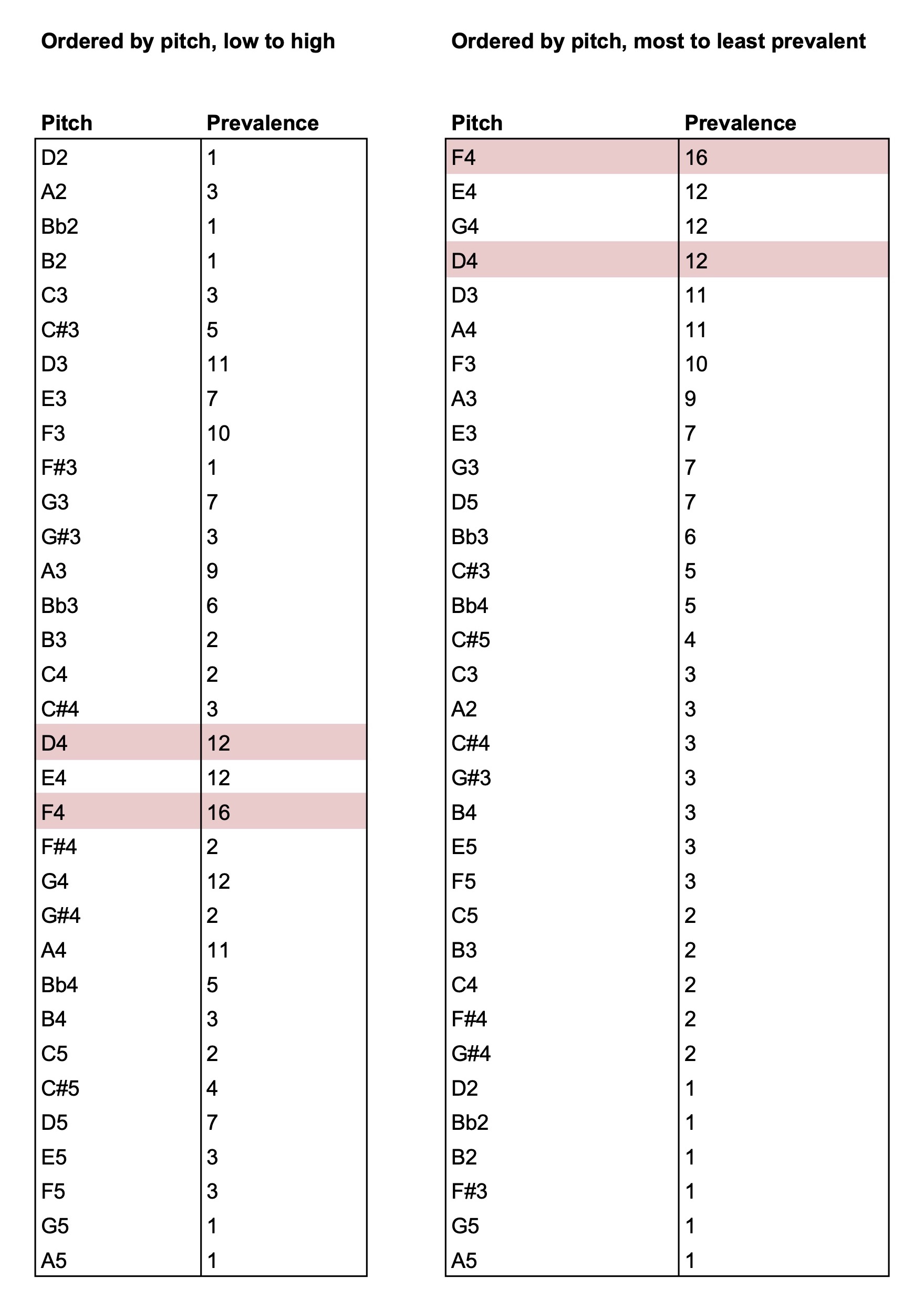

To start, I counted the occurrences (prevalence) of each pitch in the Prelude BWV940:

In the table, the ‘central’ tonic pitch of D4 is highlighted, and the most prevalent pitch, F4. I chose F4 to be the central axis of this performance. In total, there are 170 notes in the Prelude (i.e. the sum of all these occurrences), but adding the Tierce de Picardie in an extra repetition gives 171 notes (more about this later).

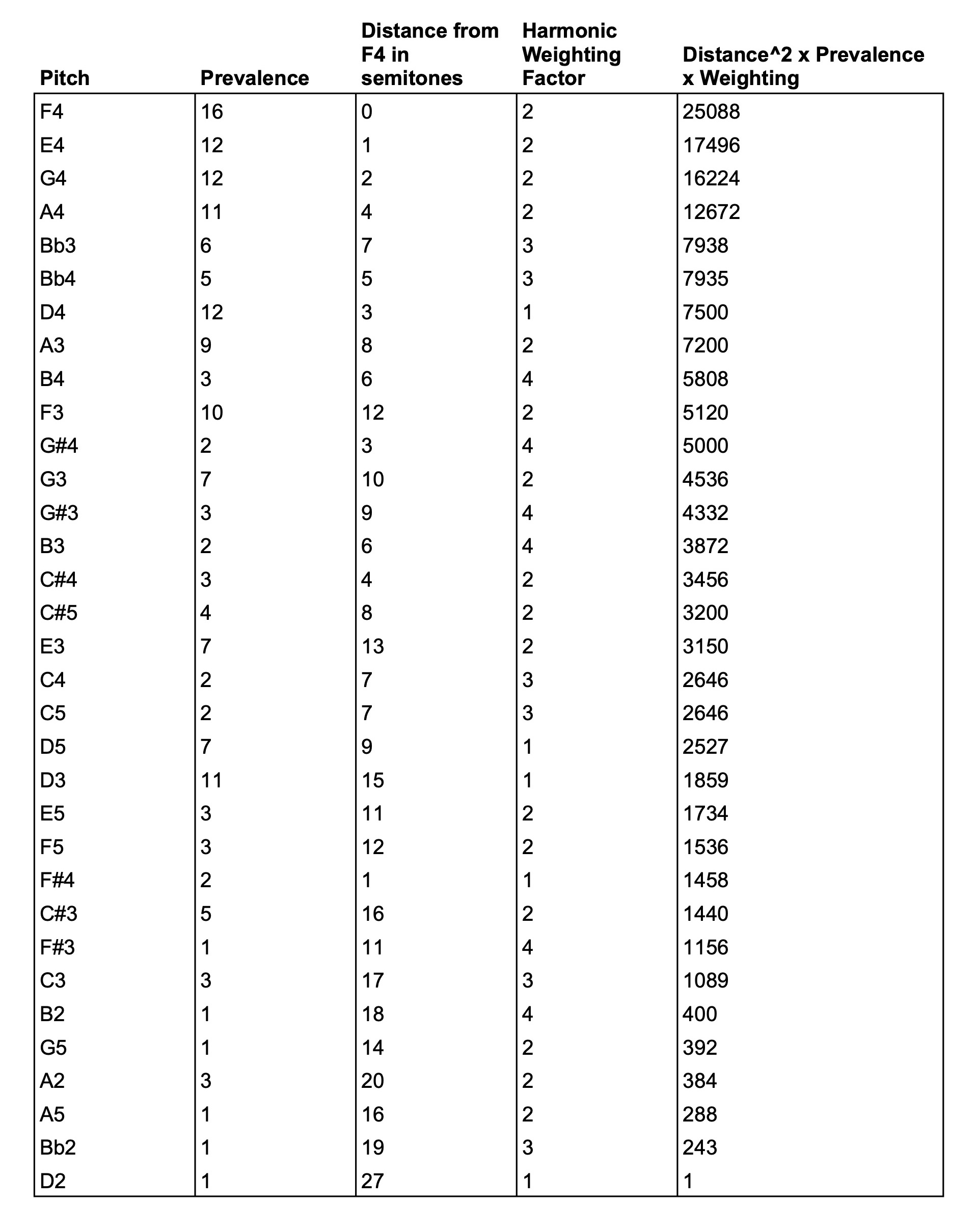

Then I calculated the distance of each pitch from this central axis F4, counted in number of semitones. I also classified each pitch with a weighting according to how closely-related each pitch, harmonically, to the tonic D minor. I called this the Harmonic Weighting Factor, and allocated the tonic pitch with a factor of 1, immediately related pitches with 2 (i.e. the pitches in the tonic and dominant triads), lesser-related pitches with 3 (the flat seventh and the sixth), and distant pitches with 4 (E-flat, F-sharp, G-sharp, B). The results are shown here:

Using these three parameters (Prevalence, Distance from F4, Harmonic Weighting Factor), I calculated the following equation:

(Distance from F4)2 x Prevalence x Harmonic Weighting Factor

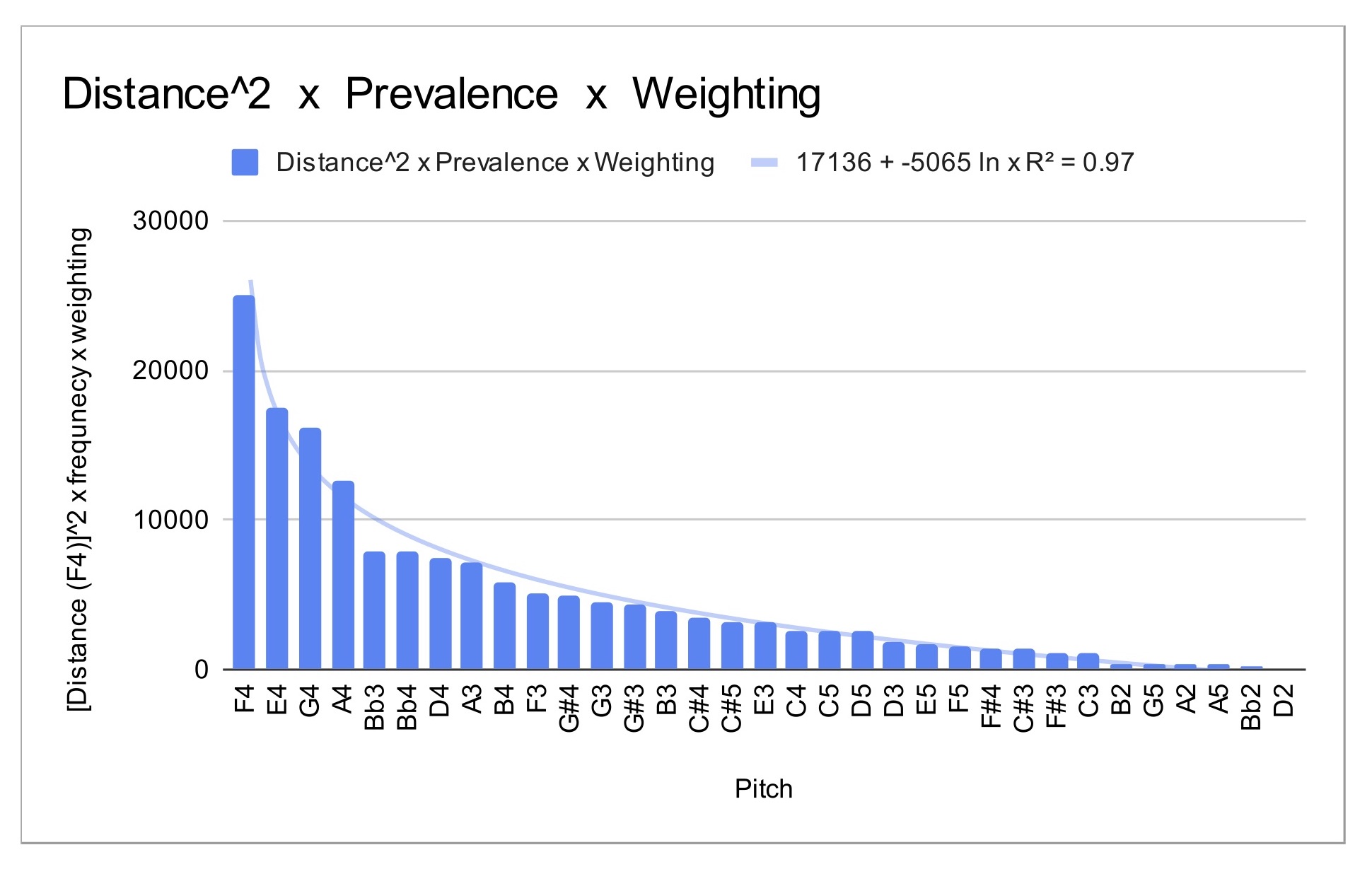

The results are in the far right hand column of the table above, and in this graph:

On this graph, my spreadsheet programme (Google Sheets) calculated the line of best fit, which is marked as a grey line on the graph. The line of best fit had an R2 value of 0.97, which means it’s a very good fit to the given data. The equation for this line of best fit is:

The concept of the performance

I decided that the total length of the performance should be about 35 minutes long, which I worked out would be 28 repetitions of the complete prelude at my preferred tempo. Each repetition would reveal a certain number of the 171 notes in the prelude, and sustain those notes until the next occurrence of a pitch in that particular voice (for the most part, there are three simultaneous voices in the prelude, sometimes four or five). By gradually unveiling pitches in each repetition, the prelude would gradually ’emerge’ or ‘take shape’ from a series of sustained notes based around F4. That, in summary, was the concept — the gradual blooming of a ‘musical flower’.

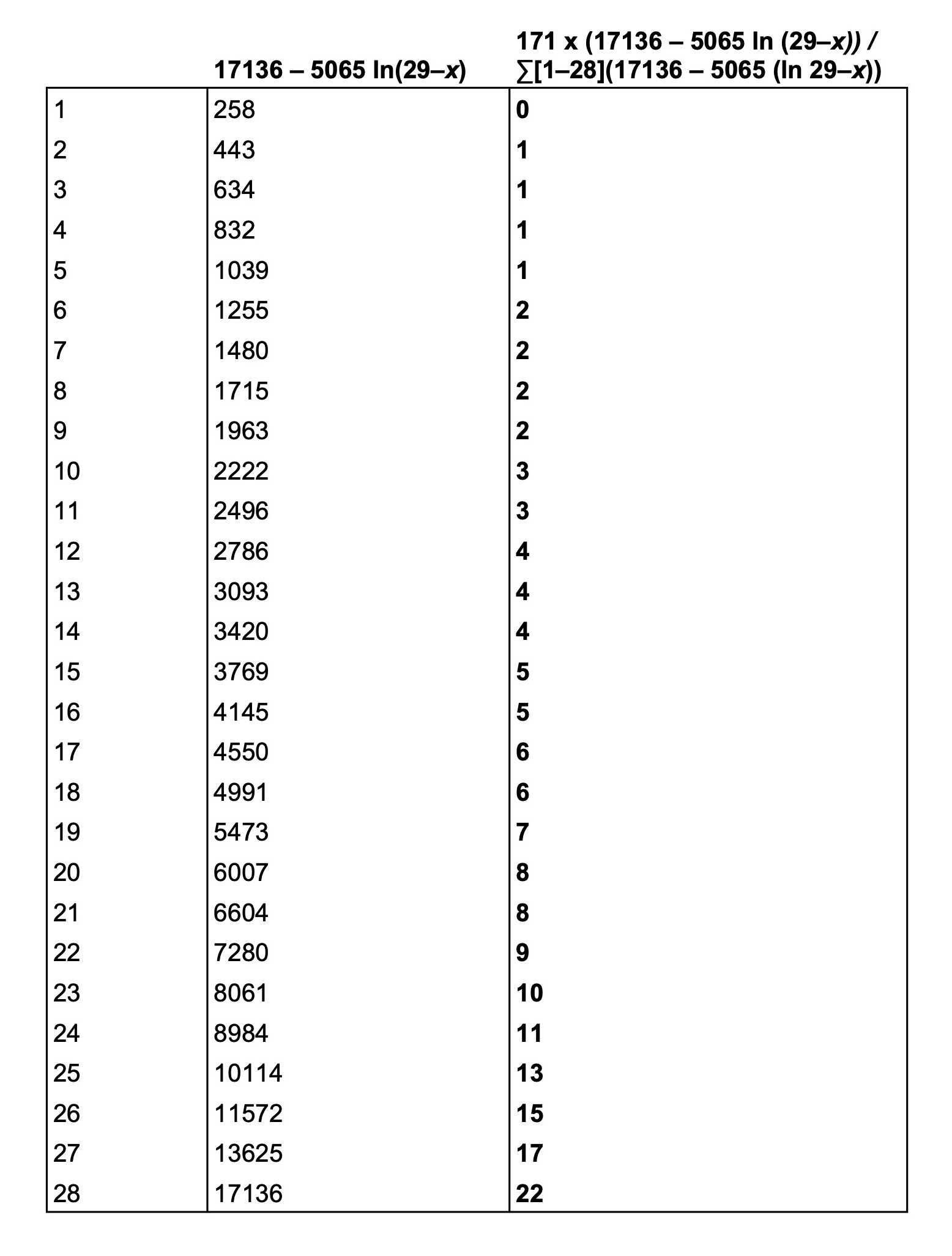

I wanted the unveiling, or blooming, to also happen exponentially, so that very few notes would be revealed at first, and this would increase through to the final repetition. I used the same logarithmic equation that was derived from the pitch analysis to map out the number of pitches that would be revealed on each repetition of the prelude. In this case, the logarithmic curve must be inverted, in order to start with a low number and end with a high one. x becomes (29–x), since I want 28 repetitions. The equation looks like:

And in order to find the number of notes revealed in each repetition, as a proportion of the total number of notes, 171, the equation is:

The table below shows the results, for each repetition from 1 to 28, rounded to the closest integer:

The pitches were ‘unveiled’ according to the chart above. For practical purposes, the value for repetition 1 was switched with that for repetition 2, so that a pitch was presented at the beginning of the performance rather than just silence (consequently there was no new pitch in repetition 2). Thereafter, 1 new pitch was presented in repetitions 3 to 5, and so on, with 17 new pitches presented in repetition 27.

For artistic purposes, an extra complete repetition was added at the end (number 29) to delay the final pitch (F#4) that forms the Tierce de Picardie. Therefore we have repetition 28 with 21 pitches and repetition 29 with just one, the F#. This, in effect, gives us two performances of the complete Prelude, without and with the Tierce de Picardie.

The pitch allocation is show in the following chart. The pitches were allocated by intuition within this chart, but two guidance lines were plotted on it to aid with pitch placement. These were linear (shaded in blue) and the same logarithmic line as found in the pitch distribution (17136-5065 Ln x) (shaded pink). Pitch distribution roughly followed these curves, in a scattered approach.