I was very fortunate to be featured this year at hcmf// across three concerts of my most recent works: Answer Machine Tape, 1987, performed and commissioned by Zubin Kanga; Numbers 81–100, performed and commissioned by Lovemusic; and My Favourite Piece is the Goldberg Variations, performed and commissioned by Andreas Borregaard. As part of that focus, writer Tayyab Amin wrote a lovely profile for the programme book, which is copied below. Please contact Tayyab here if you would like to license this profile for other uses. The article on the hcmf// website can be seen here.

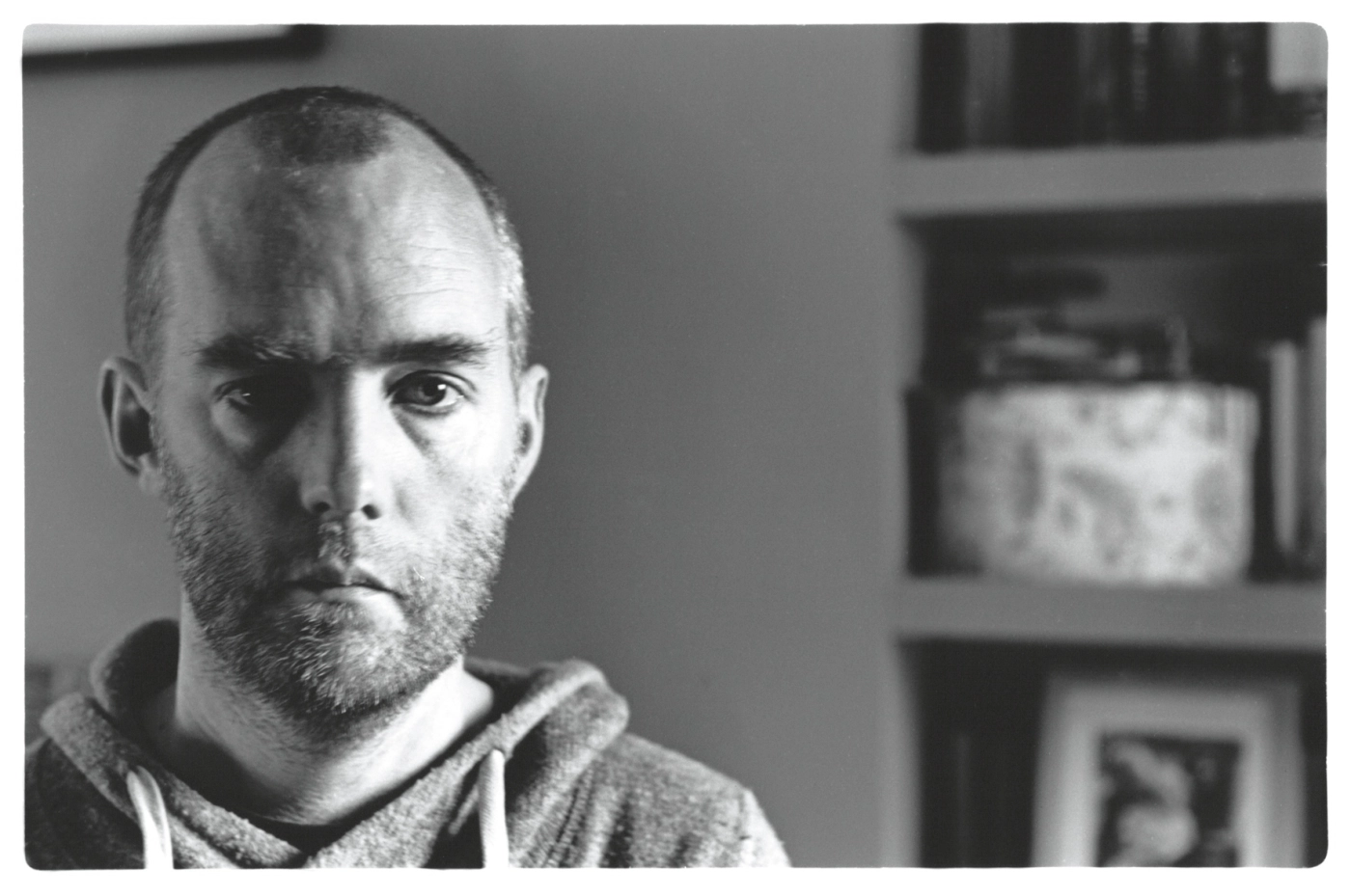

Philip Venables’ personal, political storytelling

Among the most fascinating of contemporary British composers is Philip Venables, whose flair for the theatrical is matched by a subversive sleight of hand that comes inherent to all natural storytellers. Recurrent themes across their works include politics, sexuality, gender and violence – motifs that do of course intertwine, though more broadly share the quality of relating to whether one lives alongside or against the grain of our society. There are all sorts of tales Venables opts to tell, from maternal memoirs and posthumously performed plays to true-story accounts of runaway teens and the vengeful reflections of world-class boxing athletes. They come in all manner of guises too: operas for adults or for children, site-specific soundworks, concertos and pieces of spoken word. Even shouted word, in some cases.

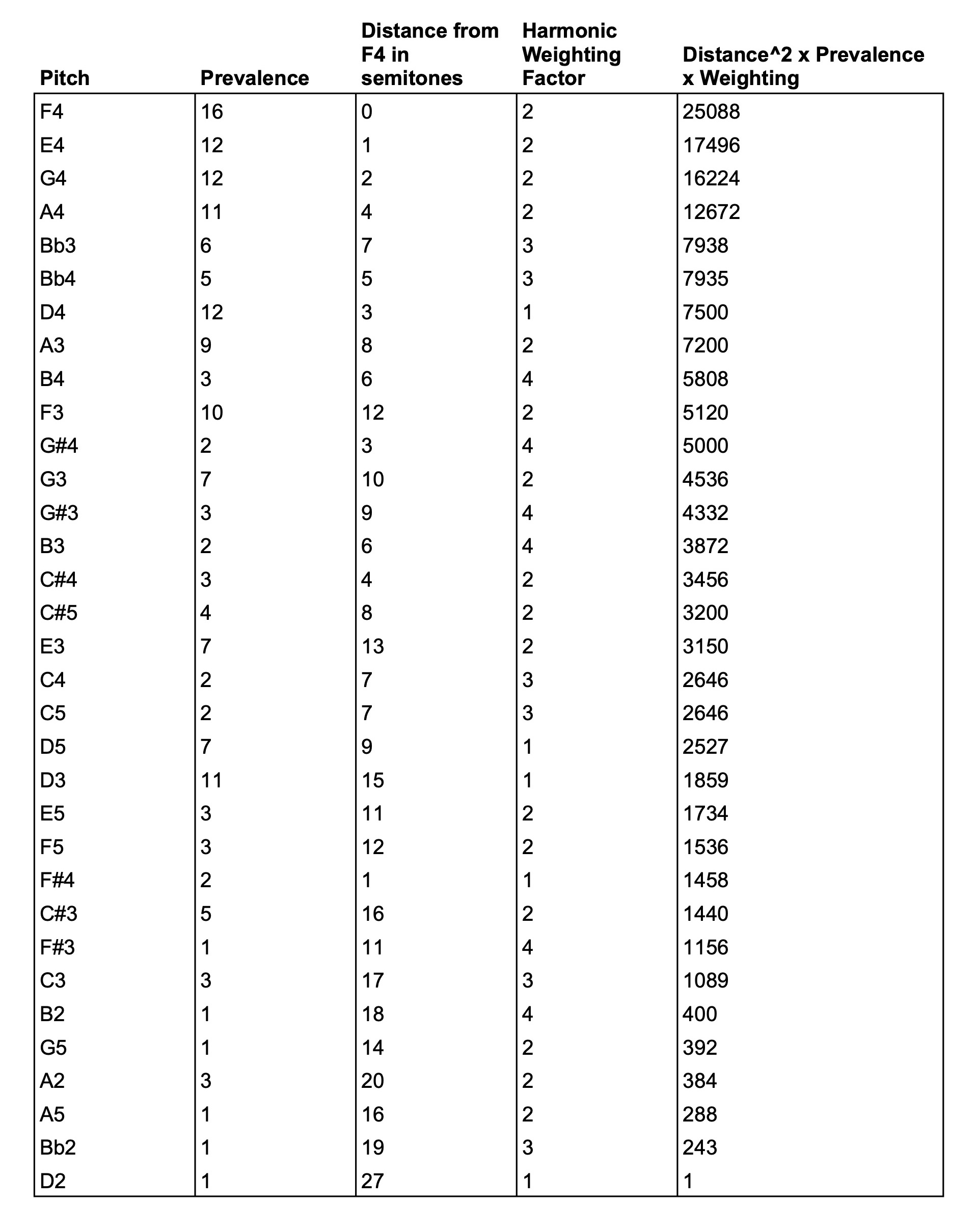

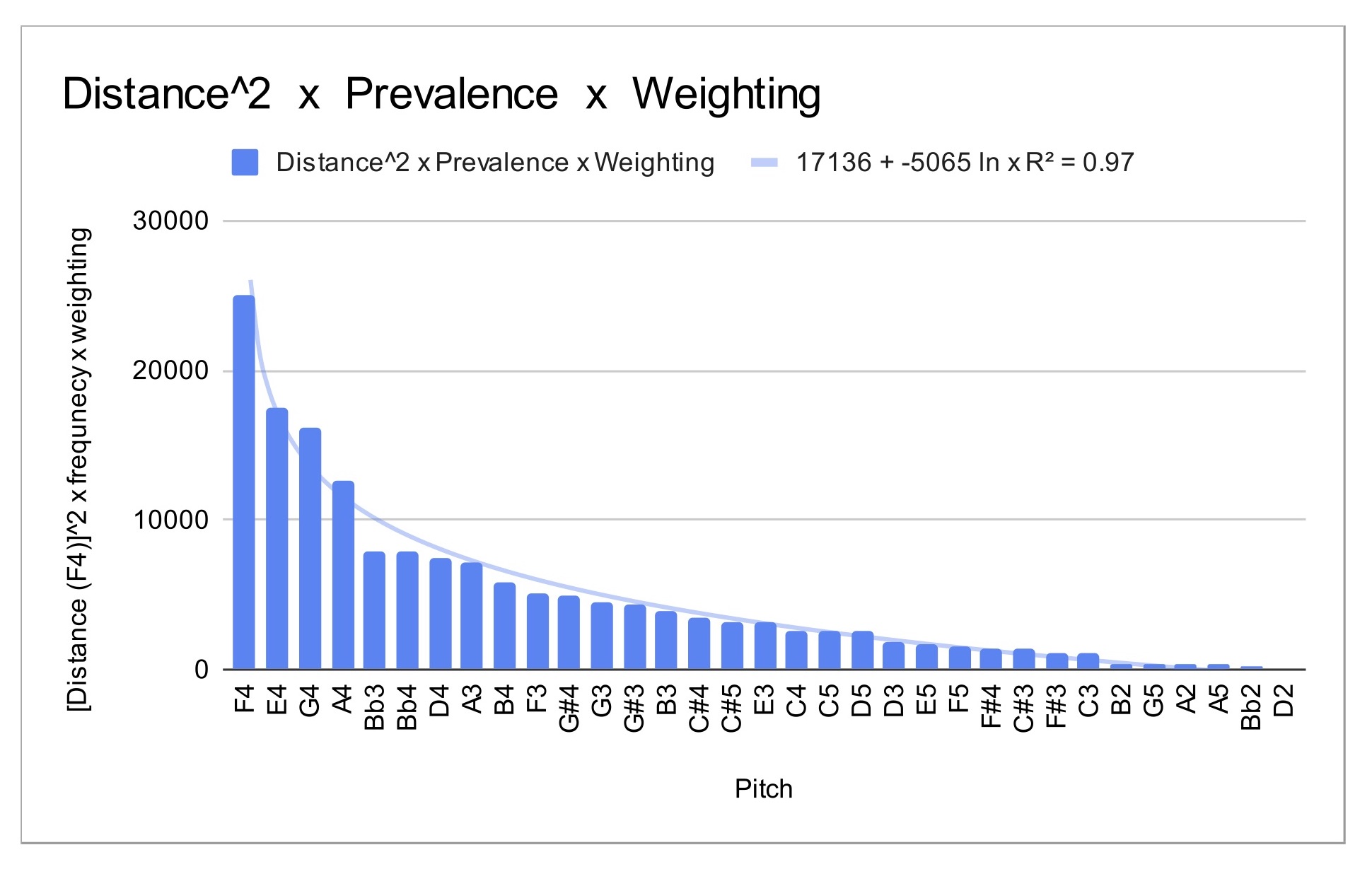

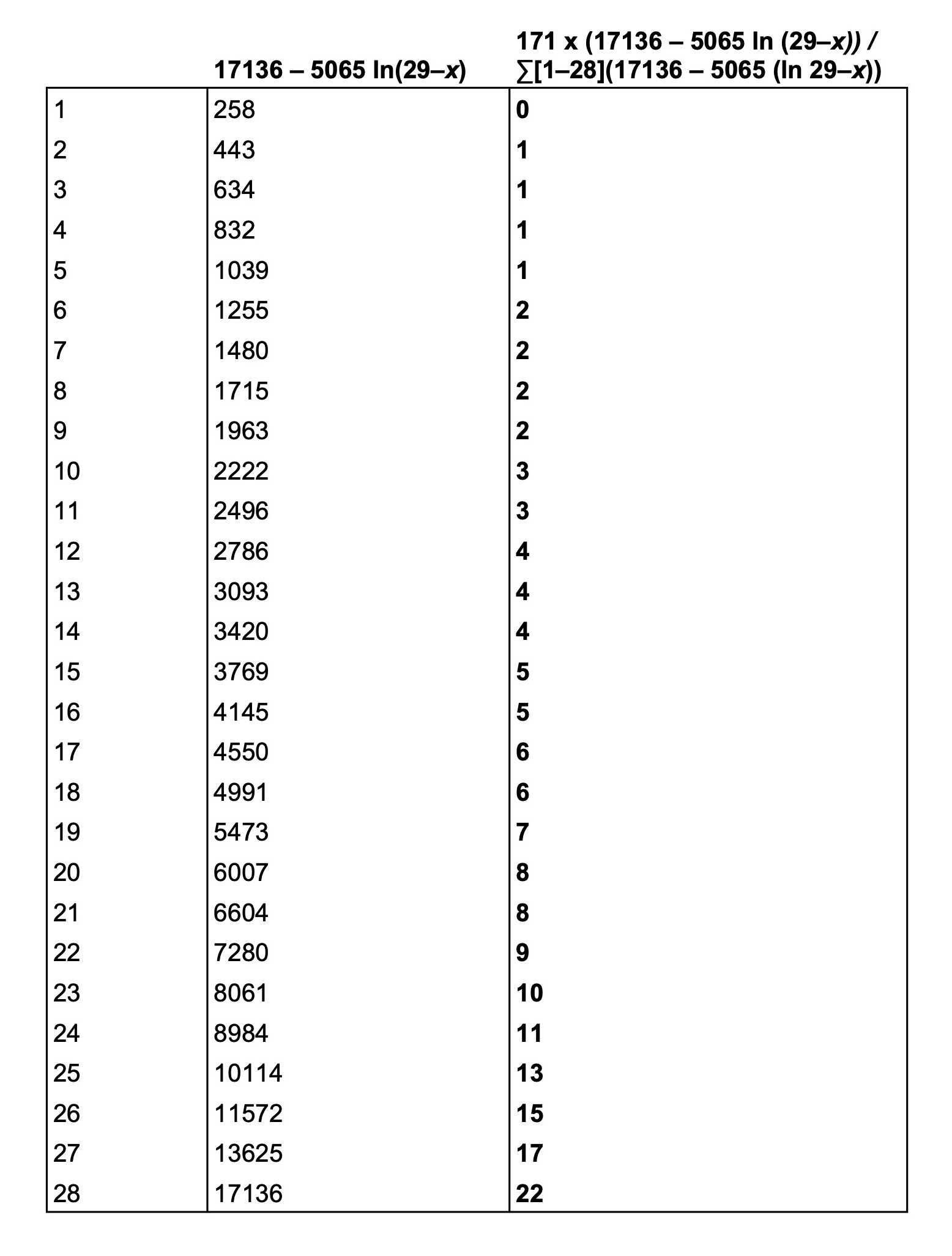

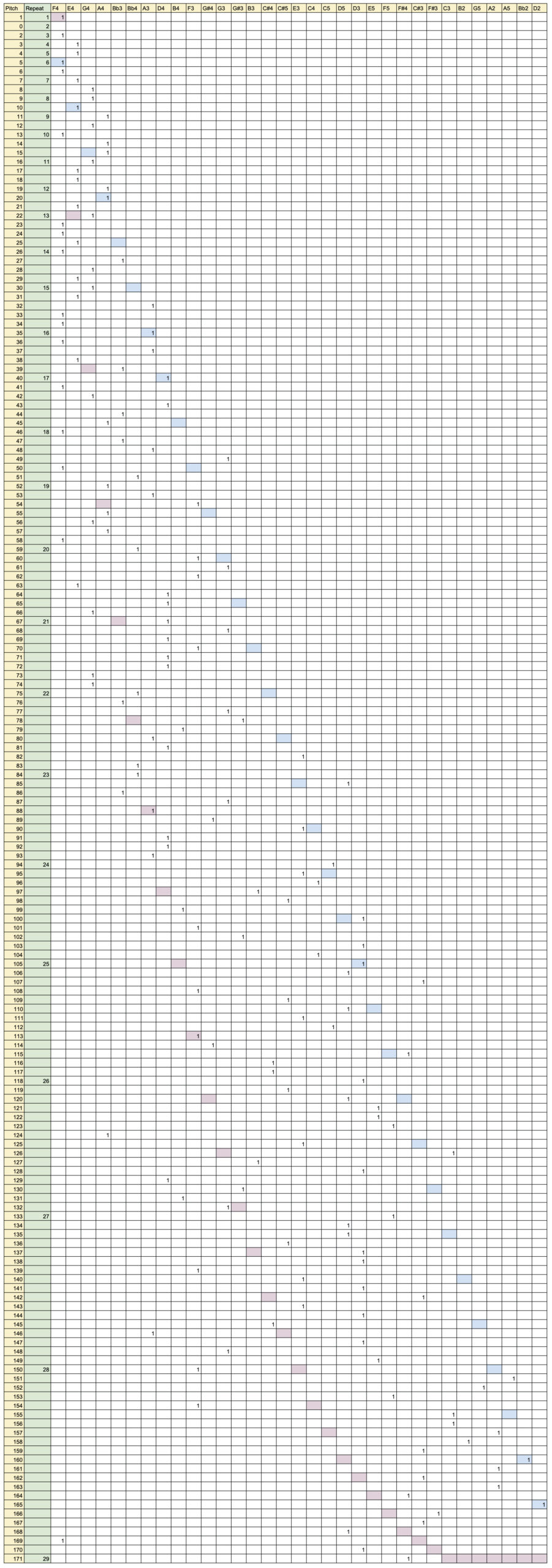

Based between Berlin and London, Venables nurtured their career as a composer and collaborative artist for several years before their breakthrough operatic adaptation of late playwright Sarah Kane’s final work, 4.48 Psychosis. Since then, Venables has established a trend of preferred elements to focus on in their compositions: working from texts as source material, immersing audiences in a multi-dimensional experiences, and inflicting or at least channelling a certain sense of violence, for example through how abrupt a work’s components are cut together, interrupting or compounding each other. There’s an intent behind such rhythmic intensity, one that Venables admits to calculating formulae for, transposing compositions from numerical spreadsheets onto musical scores.

One text Venables is compelled to return to is Simon Howard’s Numbers, first in 2011 and as recent as 2021. These poems traverse seemingly vivid memories that devolve into onomatopoeic fervour, streams that wander to the brink and back again. Venables has described them as ‘unfussy, evocative, violent and visceral’ – attributes they look for in music too. These qualities are evident in the setting of these poems of course. Take Numbers 91-95, where the speaker’s account is interrupted by their own sudden outburst as harp, woodblock and flute resist interjecting and lucidity slips from view. The text and music aren’t driven by narrative, but their colour and imagery, the political brutality and fractured hardness of them speaks volumes. We’ll see a comprehensive demonstration of the dynamism of verbal expression as Strasbourg-based new music collective lovemusic perform a selection of works from the Numbers series as part of their programme at hcmf// 2022.

Venables’ compositions aren’t always written for typical chamber instrumentation – there’s often a multimedia element to their works. Also appearing at this year’s festival is the recent solo piece Answer Machine Tape, 1987. Teaming up with frequent collaborator, dramatist Ted Huffman, as well as software programmer Simon Hendry and innovative pianist Zubin Kanga, Venables devised a work for piano where keystrokes are detected and input to software through MIDI detection and MaxMSP. This transforms pianist into transcriber and annotator, developing an archival, perhaps parasocial storytelling relationship with recorded and projected source material: the answer machine tapes of New York visual artist and activist David Wojnarowicz. These recordings capture the last days of Wojnarowicz’s former lover and close friend, photographer Peter Hujar, where the banal snippets of everyday life in a setting of artistic vibrancy and gay expression are loomed over by the onset AIDS crisis. Contrast to the technologically mediated interfacing at the crux of this work, Venables presents unflinching intimacy as both invitation and challenge.

Much like Answer Machine Tape, 1987, the accordion piece Andreas Borregaard is due to perform at hcmf// takes verbatim audio material and negotiates the levels of their directness with their conversational quality. Yet in this composition, titled My favourite piece is the Goldberg Variations, interviews come from the personal life of Borregaard’s mother Susanne to more actively explore the accordionist as storyteller.

As long as there are stories to be told, Venables will discern new ways to share them in whoever’s voice they can – even if it takes a full reset on creating abstract music following a stint composing for opera. Their role is to challenge both the politic of the status quo and our intrusive storytelling intuit in one fell swoop.